Whenever I put together a course, I like to imagine that there’s some sort of narrative thread running through, whereby early topics and readings lead to the ones that follow. Sometimes that thread is brute chronology, but most often, it’s thematic, and I suspect that more often than not, the thread is one that only I can see, although I do try to suggest it at various points during the semester. In the case of RCDH, this has been a little tricky, not least because DH is still emergent, somewhat interdisciplinary, and my own field’s engagement with it is uneven. In my head, though, after we’d gotten an obligatory week of definitions out of the way, the first “unit” of the course was a trio of weeks gathered under the headings of database, archive, and metadata. (Here’s the schedule, if you haven’t seen it.)

We’re turning now to a week that didn’t necessarily fit that well as I was originally putting the course together, a week that combines Stephen Ramsay’s Reading Machines, some work on procedural literacies, and a few pieces/performances of algorithm. It’s an ambitious little week in its own way, but as we were working our way through a discussion of metadata last night, it got me to thinking about the transition between this week and next. Some of this I raised in class somewhat tentatively, but I wanted to write through it a bit today, partly for my own memory, and also because my guess is that there are others who have written about these ideas in more detail, whose work I may not have come across. So if any of this happens to resonate with other texts, please leave a note/suggestion in that regard.

If I have a hypothesis here, it’s that there’s an important connection between metadata and proceduracy (or procedural literacy) that I haven’t thought through as carefully as I want to. My own background/familiarity with the scholarship on metadata is a little spotty, so I worry that this is obvious to everyone other than me. I’ve read some of the classics, like Sorting Things Out, and I came to the topic through the Web2 discussions (like Everything is Miscellaneous), enough so that when I was in charge of the CCC Online Archive, we billed ourselves as an archive of journal metadata with a mix of approaches (mixing established classification schemes with emergent tagging, etc.). If I had to pin down a couple of dominant themes in the literature I’ve read, there was a focus in the mid-2000s on taxonomy vs folksonomy, and I think that’s an ongoing conversation. More recently, given mass digitization efforts, the quantified self movement, revelations of deep surveillance, and the proliferation of online archives, my sense is that there’s also been a turn towards the more basic question of accuracy, both in terms of getting it wrong and getting it too right. For example, last night we discussed Geoffrey Nunberg’s critique of Google’s Book Search, which chronicles some of its (many) egregious metadata failures and Jessica Reyman’s piece in College English on user data and intellectual property (PDF). Nunberg is a pretty straightforward critique of the consequences of getting metadata wrong, and Reyman (following Eli Pariser’s Filter Bubble) might be described as an exploration of the hazy line between data and metadata. Reyman closes by explaining that

The danger presented is that the contributions by everyday users will potentially be transformed into increasingly exclusive forms of proprietary data, available to the few for use on the many.

FB and others have become so adept at collecting and analyzing metadata that “privacy settings” are increasingly an empty gesture, a point that’s also illustrated charmingly by Kieran Healy’s “Using Metadata to Find Paul Revere,” another of last night’s readings. The connective tissue for me here is referentiality–the degree to which metadata presents us with an accurate representation of the data it is purportedly about. Referentiality is also one of the goals (among others) of various metadata standards, like the work that Cheryl Ball and the Kairos folk are doing.

One of the themes that emerged for me, though, during the discussion was the degree to which there’s a tension between (to borrow the subtitle of Sorting Things Out) classification and its consequences. That’s certainly a theme in Tarez Graban’s “From Location(s) to Locatability: Mapping Feminist Recovery and Archival Activity through Metadata,” (no link, sorry) which works from the assumption that metadata makes certain activities more visible and others less so, and that recovery work can proceed from questioning and complicating the categories that we often internalize about academic work.

I think, though, that I want to push that tension into the heart of metadata itself, something more like what Curtis Hisayasu gets at in one of his contributions to “Standards in the Making“:

What becomes absolutely transparent in these intersections is the actual work of historical knowledge-making which involves not simply “digging up” artifacts and placing them accordingly in the container of linear time, but making self-conscious decisions about how that artifact is to be organized alongside others to produce a narrative and an argument about the present. “Tagging,” in instances such as these does not so much “describe” digital artifacts as much as it appropriates them and composes them in the name of more general logics of history and identity.

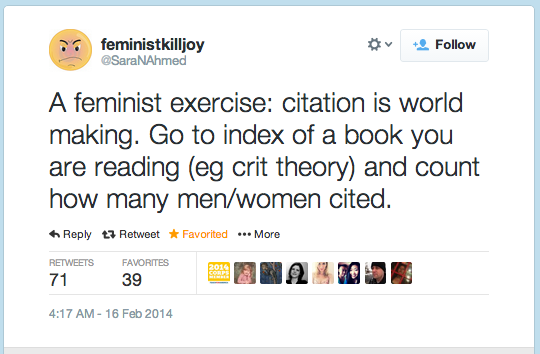

I don’t think that I’m after the claims, made variously throughout our readings last night, that metadata is necessarily rhetorical, ideological, and/or political, although I do think that it is all those things. In its nature as description, all of those qualities follow for me with respect to metadata. Maybe I’m pushing at something that is obvious or implicit in those adjectives, but I feel like there’s also space to think about procedurality in ways that might not be immediately apparent. Over the past few days, a couple of Twitter “events” helped this coalesce for me. First was Anil Dash’s essay about his “experiment” in retweeting, where he made the decision to tweet only women, and the second was Sara Ahmed’s discussion of gender and citation (in my head, I think of this as an essay on “Works Slighted”):

Ahmed’s not the first to point this out, nor are academic bibliographies the only venue where this (important) discussion is happening, nor is this solely a gendered concern, but her post(s) happened to coincide for me with this sense that metadata contains, at its heart, a ratio between description and procedurality. That is, there is no description degree zero, no purely descriptive metadata, and I think that sometimes we fall into the trap of imagining that there is. It’s not enough to simply say “it’s both,” though–I think that claim is easy enough to accept. The procedural literacy of metadata lies perhaps in figuring out that variable ratio and tuning it to the task at hand.

The exercise with which we began class last night was to take a couple of pages from an old MLA job list, and to develop a set of metadata categories based upon the entries, and one of things that crystallized for me was the degree to which this ratio varied from term to term. We also were able to lean on the ratio a bit, such that a seemingly descriptive phrase like “residential campus” could be read as a subtle (seductive) means of distinguishing an institution from others (vs. commuter campuses, online delivery, et al.). And on Sunday, I’d already taken an otherwise procedural term like “postmark” and used it as a descriptor for the impact of technology on the process. The deeper into the exercise we got, the more I think we were thinking both in terms of what metadata represent and how they functioned.

That same ratio lurks at the core of the bibliography, which is both descriptive (here are the works I have cited) and procedural (presented in a consensual format for their location), but Ahmed, Dash, and many others call attention to the procedural consequences of the bibliography. What we know now about network effects and filter bubbles should attune us to those consequences, even if we haven’t personally run afoul of the disciplinary fatalism that Ahmed describes in her followup to the Twitter conversation.

With respect to bibliographies, there’s an additional, material, fatalism–the reason we have traditionally constrained bibliographies to the works directly consulted for a given piece of writing is for reasons of space of the printed page. With the notable exception of the bibliographic essay, whose works cited sometimes also concerns itself with field coverage, there is an assumption that the bibliography must be primarily descriptive–these are the texts named directly here. But that list of citational attachments is, of course, implicitly preferential. As Ahmed puts it:

There is a ‘good will’ assumption that things have just fallen like that, the way a book might fall open at a page, and that it could just as easily fall another way, on another occasion. Of course the example of the book is instructive; a book will tend to fall open on pages that have been most read.

Maybe what I want to say is that there’s a similar assumption at play within metadata, or more precisely, within the way I’ve traditionally thought about metadata. As our work migrates slowly away from the printed page, it might open up opportunities for tuning the ratio away from description, for embracing the compositional implications of tools like bibliographies. Not that there aren’t important issues of preservation and persistence if we were to replace static bibliographies with links to a public Zotero folder, for instance, but I find myself thinking more and more about experimenting this way.

Geez. There’s plenty more to say, but this is long enough as it is. I don’t suspect I’ll have the time, energy, or inclination to do this every week. And please, if you’ve made it this far, and have suggestions in mind for other things I might stir into this mix, feel free to add them below…

geekymom

February 18, 2014 7:45 pmVery interesting. I think about these things a lot and there’s a lot here. I don’t have much to add, certainly not in terms of more texts. A couple of things. Computationally, there’s often not a lot of difference between data and metadata. In fact, one of the critiques that’s been lobbied at the Obama administration is the this “just metadata” idea is crazy. Sometimes the metadata reveals more than the data itself. A picture, for example, might be elusive about it’s location in the photo itself, but it’s metadata reveals the GPS data. Here’s an article about that (http://blog.internetcases.com/2014/02/04/no-privacy-interest-in-photo-metadata/). You seem already headed in that direction. Where once only the metadata was easily accessed by machines, now all the text and other data, maybe even edits? are available.

Second thought, I’ve recently found myself on the receiving end of gender bias connected to the procedural impact of online media. It was kind of weird. It was one of those things where if one searched Google, let’s say, my name and 4 men would appear, perhaps with the 3 of the men appearing above me and one below. Rather than say, invite 1 guy and me to speak, the 3 men were selected. There could have been other reasons, of course, but it’s relatively clear that gender had something to do with it, not that the person/people was being biased but because the way the internet work, more is better. Does that make sense?

Increasingly, I think, people are assuming that the technology is neutral, when it’s clearly not, and often reinforces existing biases. Maybe that’s too simple a conclusion, but I guess the real work is in figuring out ways of constructing metadata so that it works against our tendencies. Dash’s experiment was a human being’s attempt at that, but the real work is in the machine.